Fungus in Chernobyl nuclear disaster zone has mutated to ‘feed’ on radiation

The fungus has adapted to convert gamma radiation into chemical energy

A species of black fungus at the site of the Chernoyl disaster has mutated to ‘feed’ on nuclear radiation that would be lethal to most life forms.

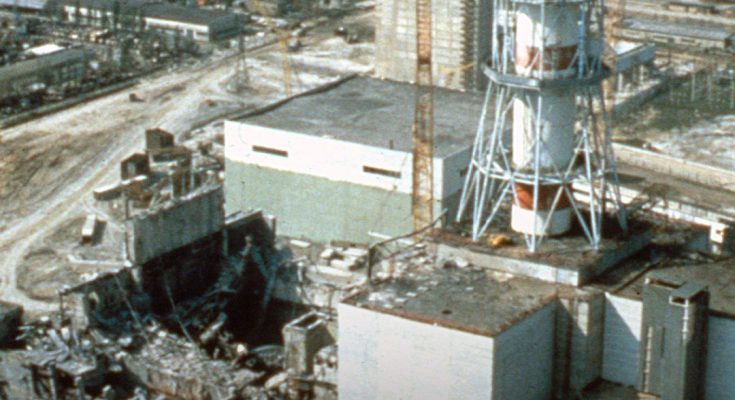

In the early hours of April 26, 1986, one of the most devastating nuclear disasters in history struck the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Pripyat, Ukraine.

Chernobyl’s Reactor 4 experienced a critical meltdown, which resulted in a number of explosions, raging fires and a catastrophic spread of radiation across surrounding areas.

Dozens of people were killed in the direct aftermath of the Chernobyl disaster, with thousands later dying due to radiation-related causes in the years that followed.

The disaster happened more almost four decades ago, but the 20-mile radius surrounding the power plant – known as the exclusion zone – remains one of the most contaminated places on Earth and will not be habitable for about 20,000 years due to the long-lasting effects of radiation.

However, while the nuclear radiation would be harmful to most life forms, a black fungus found at the site has adapted to ‘feeding’ off it.

Scientists have found a black fungus that had adapted to ‘feed’ off nuclear radiation at the site of the Chernobyl disaster (Igor Kostin/Laski Diffusion/Getty Images)

Radiation-eating fungus: how does it work?

Cladosporium sphaerospermum is a highly resilient species of black fungus that has been observed growing on the walls of Chernobyl’s Reactor 4 since the disaster.

Scientists have found that the fungus has mutated to use nuclear radiation as a source of energy in a similar way to how plants get energy from the sun.

It gets its radiation-eating power from melanin – the pigment that gives humans their skin color and acts as a shield against harmful UV rays.

But, the fungus ‘does more than shield: it facilitates energy productions,’ according to Rutgers University evolutionary biologist Scott Travers. This process, in which melanin absorbs radiation and converts it into chemical energy, is known as radiosynthesis.

The fungus converts radiation into chemical energy in a process known as radiosynthesis (Getty Stock Images)

Fungus could hold the key to better space travel

Now, scientists hope they may be able to harness this process to create radiation shields that can protect astronauts during deep space missions.

Harsh radioactive conditions in space is a major hurdle in long-term missions, with astronauts being exposed to the equivalent of one year’s exposure on Earth in just one week on the International Space Station (ISS).

And, according to the European Space Agency (ESA), an astronaut on a mission to Mars could be exposed to doses of radiation up to 700 times higher than on our planet.

Researchers aboard the ISS have studied cladosporium sphaerospermum’s ability to reduce the effect of harmful radiation in an environment similar to Mars’ surface.

They found that that the fungus blocked and absorbed 84 percent of the space radiation. The fungus also showed significant growth over a 26-day period, suggesting its ability to perform radiosynthesis could extend to space environments.

Featured Image Credit: Getty Stock Images/Igor Kostin/Laski Diffusion/Getty Images

Topics: World News, Science, Chernobyl

Bec Oakes

Dogs living near Chernobyl nuclear disaster zone have developed a ’super power’

It’s believed the strays are the offspring of dogs left behind after the evacuation

Lucy Devine

Dogs near the Chernobyl site have developed a ‘super power’ after living so close to the disaster zone.

On 28 April 1986, the flawed Number 4 reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine exploded, releasing at least five percent of its radioactive reactor core into the environment.

Following the disaster, dozens of people died within a few weeks of the explosion, and approximately 350,000 people were evacuated from the area surrounding the plant.

The disaster occurred in April 1986 (HONE/GAMMA/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Although the explosion happened many decades ago, it still remains relevant to this day, with the event continuing to impact those living nearby.

For example, stray dogs living in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ) – which is the radioactive area surrounding the nuclear plant – may have actually adapted to the toxic environment.

A new study collected blood samples from 116 stray dogs in the area and found they had managed to not only adapt to the environment, but thrive in it too.

“Somehow, two small populations of dogs managed to survive in that highly toxic environment,’ said Norman J. Kleiman, environmental health scientist at Columbia University.

“In addition to classifying the population dynamics within these dogs… we took the first steps towards understanding how chronic exposure to multiple environmental hazards may have impacted these populations.”

The findings were published in the Canine Medicine and Genetics journal back in March 2023.

The strays are likely to be offspring from dogs left behind during the evacuation (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Scientists found that the stray dogs had a number of genomic locations – which are essentially the positions of genes within chromosomes – that varied from the rest of the genome.

Researchers said that 52 genes ‘could be associated with exposure to the contamination of the environment at the Nuclear Power Plant’.

The findings could suggest that the contamination has caused the dogs – who are likely to be offspring from dogs left behind by the evacuation – to develop mutations allowing them to adapt to their environment.

The study is just some of the research being conducted into the site and whether animals and humans could safely one day return.

The findings could suggest that the contamination has caused the dogs to develop mutations (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Earlier this year, scientists discovered wolves living in the zone were resilient to the radiation that causes a number of different cancers.

Meanwhile, in March, experts visited Chernobyl to investigate nematodes, which are tiny worms living in the soil.

Despite the obvious high radiation levels, the genomes of the worms were not damaged at all.

Dr Sophia Tintor, lead author of the study, said: “Chernobyl was a tragedy of incomprehensible scale, but we still don’t have a great grasp on the effects of the disaster on local populations.

“Did the sudden environmental shift select for species, or even individuals within a species, that are naturally more resistant to ionizing radiation?”